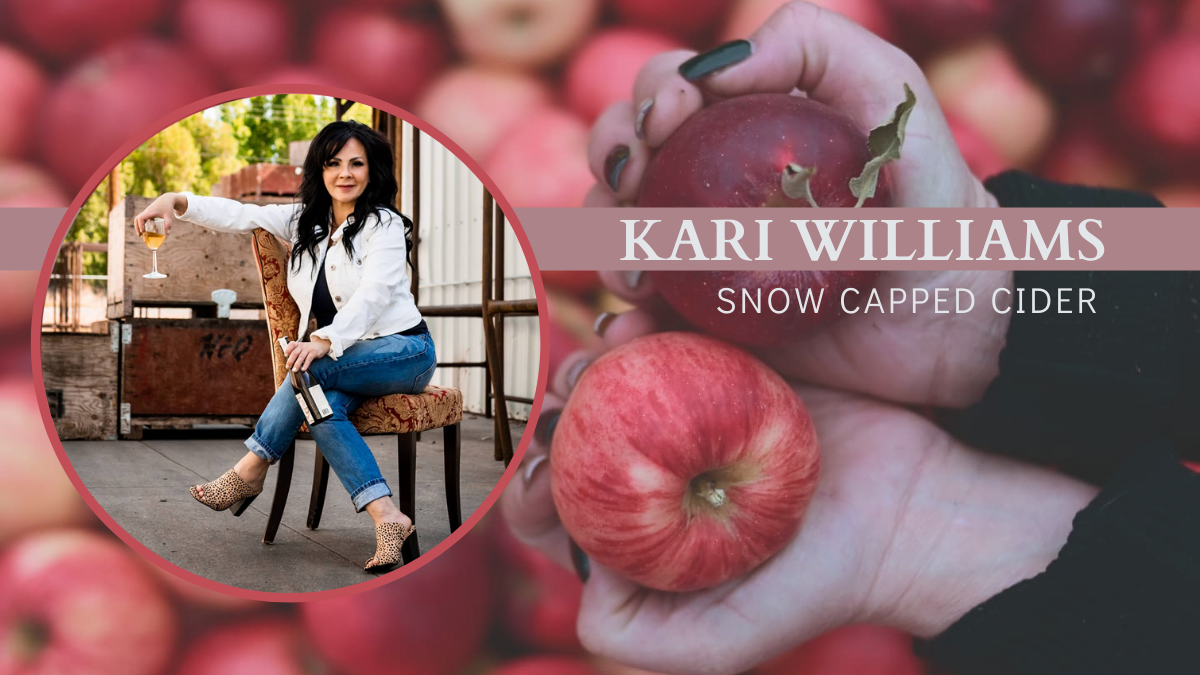

We all know what to do when life hands you lemons. For Kari Williams, who married fourth generation orchardist Ty Williams, when life handed her apples, she learned to make cider. It was Ty’s great-great-grandfather, Pap Williams, who first established an orchard high up on Colorado’s Western Slope. Now, three of Kari and Ty’s four kids work full-time at the state’s largest fruit growing and packing (and fermenting) company. At 6,130 feet, it’s at a significantly higher elevation compared to America’s largest apple regions like Washington’s Yakima Valley and New York’s Hudson Valley.

Kari Williams has no formal cidermaking training. In 2014 the wine and culinary enthusiast studied hard, experimented ad nauseum, and built up a team of expert fermentationists en route to launching Snow Capped Cider.

Her devotion has paid off. At this year’s ultra-prestigious Great Lakes International Cider and Perry Competition (GLINTCAP), Snow Capped took three best-in-shows in the heritage cider category. The first was Snow Capped’s Harrison, a sparkling cider that hails from the new 750-ml Reserve Series, each named for its heirloom varietal. Trailing two places behind was Gold Rush, Snow Capped’s canned blend of five heirloom varietals, all of which are prominently listed on the label..

Of course, this is not the first time Snow Capped has been honored. Among their other decorated ciders (which date back to 2017 but seem to increase exponentially) are three platinum medals awarded by the Great American Cider Competition: Harrison, Dabinett (also from the Reserve Series), and Wickson Crab (from the 375-ml Specialty Series).

It’s time to discover Colorado’s “branch to bottle” cidery rooted in family tradition but with its collective head in the clouds.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I figure there’s a reason most apple orchards are at or near sea level. What are the challenges and benefits of growing at over 6,000 feet?

We’ve been growing and packing fruit for over 100 years and five generations. We’ve really seen the effects of climate change. Drought. Fires. Freezes. A 15-minute hail storm can devastate our crop. Harsher springs means it’s more labor intensive. We’re seeing bloom times change. And water from the Grand Mesa’s snowmelt makes no stops; there’s no water treatment. We’re in a desert environment. Spent 60 years piping our orchard, water comes from direct snow melt. But growing at this elevation makes our fruit amazingly hyper-expressive and flavorful because it causes the fruit to think they’re in distress.

Many cidermakers barely have access to heirloom varietals. How many different heritage apples do you grow and how do you manage them given your climate?

We have almost two million trees, but of them over 200,000 are cider apple trees — and that’s after we lost 150,000. We have around 19 cider varietals. I’m growing cider varietals from England and France. That’s across more than one location. We have about 800 acres total, plus more down in Lubbock, Texas. I don’t have all our cider apples all in one area; I sneak them in here and there because fruit packing is the primary part of our business. Harvesting cider apples is different. And it’s actually very different to compare apples to apples. It comes down to your interpretation of the apple. Washington Dabinetts are hardly recognizable compared to my Colorado Dabinetts. Even in my terroir another grower may have an Ashmead’s Kernel but it comes down to growing techniques, grower’s skill and finishing. I juice once per year on French presses then use it all year as we’re an estate cidery.

After trying some of your products, which I thoroughly enjoyed across the board, I was immediately struck by the pear brandy–aged Blanc Mollet. How do you explain why the Harrison is the one that pleasantly haunts me?

I was smitten with that apple! Blanc Mollet is my romantic little French girl, but there’s a reason my bulldogs are named Kingston Black and Harrison. I have a grandson named Harrison. That cider is so crisp and balanced. I’ve planted Harrys, but they were little guys, not mature, and I wasn’t sure they’d thrive so I got anxious and purchased a tote from Cider View in Yakima Valley. The October freeze wiped out many of my Harry trees. But I do not give up easily! I planted an additional four-and-a-half acres of Harrison this spring so the Colorado Harrys I got out of this year’s crop are continuing to work some Harry magic. And to think, my Husband, a fabulous cider maker, thought Harrison (the Reserve cider) wouldn’t amount to much.

So you believe not only in yourself, but in your apples. Where will they take you next?

I love French and English apples, trialing different ones in our orchards, even though they’re low yield. (We’ve done Spanish-style sidra but didn’t market it well so it didn’t sell well.) Personally, I think what Colorado does to Dabinett is wonderful. I grow it in volume. Absolutely adore it. Not many people make cider with it. Ours is rich, has a buttery note, is light on tannins, and is pétillant. It’s the bottle that I grab and drink out of an expensive wine glass. When we released 750s, we showcased 100 percent single-varietals, estate-grown apples from a fruit grower’s perspective. It’s a labor of love for me. I have control over every single aspect of our cider. I don’t use anything artificial. I have the luxury of time. The apple tells me what it wants to be.

Looking for the perfect w

Looking for the perfect w

BREAKING NEWS

BREAKING NEWS