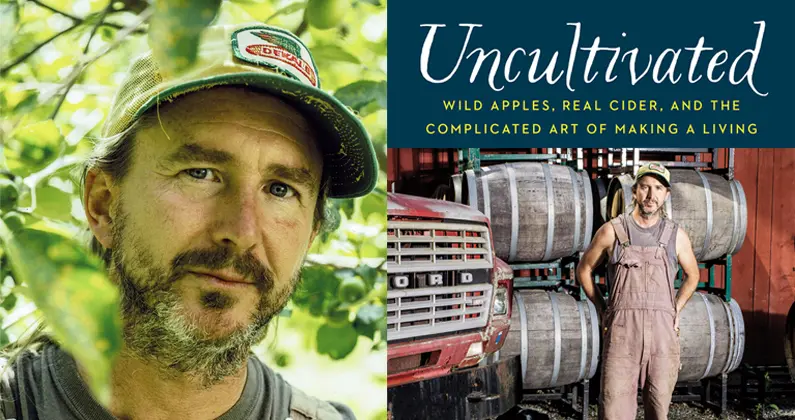

Hoping to teach amateur cider drinkers a thing or two about the making of cider, Andy Brennan has a deep infatuation with apple trees and cider and spotlights that in his new book “Uncultivated.” The author and cidermaker/owner of Aaron Burr Cidery, Brennan’s book is devoted to apple love, a refreshing look into the world of cider and everything that goes into producing it.

In this, he aims to reconnect with what he calls the “old cider culture.” We chatted with Brennan from what got him into cider to discussing the value of apple trees, the current cider scene and his call to defend the “knowledge, significance and beauty” of old ways.

What got you into cidermaking and apple love in general?

In 1994 I discovered an abandoned orchard near an old plantation house in Southern Maryland. I used to go there for peace, to paint, to forage or simply commune with the trees. Ever since then I wanted to keep exploring and learn more about apple trees because of the way they make me feel. Cider is simply part of that.

How would you describe your book and why was it important for you to write?

“Uncultivated” is about seedling apple trees — which some people call “real apple trees” — and the making of traditional cider — which some people also call “real cider”. The book draws further parallels between those things and the lives of the people. But what’s important is that “Uncultivated” is absolutely not about the farms or farmers alone, in fact I especially spotlight how these things are all interconnected to the larger culture and the mechanics of modern society. The type of apple life I’m talking about is bucolic, for sure, but it’s meaningless unless it’s anchored in the “real world.”

In your book, you discuss the importance of apple trees in your life, how have orchards influenced your life?

Specifically I write about wild trees and how they have influenced me. To be clear, these are very different trees than the ones growing on modern apple farms. I could write the rest of my life and still not sum up the differences between them, but I what I can do is sum up what those wild apple trees mean to me: they are role models. They taught me to question conventional wisdom — such as conventional agriculture, commercial cidermaking and the typical business model — and they showed me how to really look at what’s there. They can teach us all how to acclimate and contribute to our location.

What made you want to write this book?

When you read about indigenous people in the Amazon you say, “We should protect and preserve their way of life before it vanishes.” But when we hear about the newest technology we get excited about that too. There’s obviously a disconnect between preservation and development, but I’m afraid our progressive nature is by far the dominant gene. We perpetually abandon ancient wisdoms for “the new and exciting.” What’s worse, somehow we write that tendency into our economy and soon find ourselves not able to care about such things even if we wanted to.

There is an old apple culture in America that still exists but it, too, is being modernized and our personal connection to apple trees eroding. I simply want to defend a knowledge, a significance and a beauty that are all endangered by our self-made economic trap.

What do you want people to take away from reading your book?

First of all, I wrote this for lay-readers, not for apple nerds or cider geeks like myself. I wanted everyday people to understand the interconnection between the apple life and theirs. But most of all, I hope everyone starts planting real apple trees again, and doing so in every location.

I hope to combat the generic advice one reads on the internet or hears from academia and the industry. The type of success I’m talking about looks very different than “the perfect apple,” and a successful tree should look different in each and every location. I want people to discover for themselves what the Tree of Knowledge has to teach us about our world.